Tomorrow: Where did Mami eat?

Thanks to everyone that contributed to Mami’s burger fund! You gave so generously that I she got to order a “combo” meal and I got to eat too!

You can still see all past stories on my portfolio where I store clips.

https://eatgordaeat.blogspot.com/

If you want to contribute to mami’s f’ing expensive ass burgers.

Yup. I forgot it was Wednesday and forgot to publish the newsletter. It’s been 101-109 degrees in this part of Northern California. Followed by an “unexpected” lightning and thunder storm that started fire season sooner than usual. So, it’s fire season here in California and the skies are aflame and it’s raining ash.

Subsequently, I haven’t been feeling well. Mami and I got caught alongside a burning ridge on the way back from Alameda. Traffic had come to a full stop. You know, so drivers could get their videos and photos of the flames for the ‘gram. We turned off the A/C and closed all the vents as the smoke seeped into the car. It was already hot from the warm summer, but the heat from the nearby fires became intense, punishing and impenetrable. It made me wonder why funds would ever be reallocated away from services like firefighters. It also made me wonder how I could cook Puerto Rican food for the firefighters.

Behind the comfort of arroz con gandules, an unsettling adult world

Sep. 17, 2018

Above Image by Dan Liberti

Violence has always been present in my culture. From the decimation of our Taino ancestors to the current loss of over 4,000 of our gente in the aftermath of last year’s Hurricane Maria, violence is always there. Appearing in shadows, on the backs of those fighting for independence, written in calligraphy on a leather belt that hung from a rusty nail in the living room, in the streets of underrepresented socioeconomic communities, in our food.

I have known violence all of my life, too. It was the soundtrack to my childhood. It’s the place I immediately go to when I am frustrated or feel I have been bamboozled. There was only one place where violence didn’t exist — the kitchen table.

Because Puerto Rican food is a “soldering” of various continent strains of genetics, violence had to happen for it to exist as we know it today. Arroz con gandules is made with sofrito, rice, pork and pigeon peas. The recao in the sofrito is from the Taino, the pork from Spain, and the pigeon peas are from Africa.

There are vivid moments in my memory banks where I remember questioning if violence was normal. Growing up in Sacramento, we lived in a one-bedroom wooden casita, with a detached garage, on a corner parcel of land that had two other houses encompassed by a single fence. The houses made a billiards-cue triangle shape. An abandoned L-shaped field gave a one-armed hug to our occupied land. I commonly refer to it as “the compound.” I don’t recall my mother ever letting me or my visiting cousins off the compound. We had more than enough room to ride our bikes within the confines of the long chain-link fence. There existed an apple tree, blackberry brambles, plum and a mighty magnolia. Mrs. Brown, our landlady, lived in the largest house and our neighbor Marianne lived in the small house in the corner.

It was summer — it seemed like it was always summer — and I hadn’t quite started kindergarten yet. I was outside jumping off a metal barstool-turned-diving board when I had to urge to make when I had to go to the bathroom. I ran through the kitchen, made a sharp left into my bedroom, quickly stole a glance at my mom and walked through to the restroom. I didn’t entirely comprehend what was happening when I looked at my mother, but had taken so much notice that the image remains vivid: My mother was helplessly on her back, eyes grotesquely bulging, gasping for air, with Vicente’s hands firmly around her neck.

Vicente was Marianne’s brother. Vicente and Marianne were extremely good-looking; born of Portuguese parents. Vicente had thick, jet black hair, a thick black mustache, skin the color of redwood trees and a manipulative smile. Marianne looked like the singer Teena Marie. Vicente and Marianne were also completely crazy, having suffered their own traumas.

It was the first time I had seen domestic violence. Until then, it usually came in muffled sounds behind closed doors.

I queried my nana to explain what I had seen. Nana stopped frying the meat in the pot, but never looked up at me. After a moment, she continued frying the meat, but never answered me. She stood at the stove and dropped the sofrito into the hot oil until it sizzled and danced. She silently rushed cold water over medium grain rice, swirling the rice around the bowl, using her hand as a sieve by emptying the water into her hand and catching any wayward rice grains. She poured the medium grain rice in the sofrito and hot achiote oil, followed by tomato sauce, sazon, Manzanilla olives, gandules and a touch of her secret ingredient, olive brine. She swirled the mixture with her enamel spoon and covered it with a lid. We sat on her porch — I sat partially on the door frame with my bare legs on the concrete, and she sat in her plastic chair.

I silently watched the nearby “Bébé’s Kids” running amok in their Airwalks, wearing their dookie gold chains, Jheri curls and Loc sunglasses. My nana embroidered a doily with a robin in flight pattern, purchased at Ben Franklin.

“Stir the rice, mija,” she suddenly said. I ran into the kitchen and lifted the lid of her bare aluminum caldero, a blast of steam releasing itself. And with her spotted enamel cooking spoon, I shifted the rice from the bottom to the top, just as she had shown me numerous times, the way to ensure the formation of the pegao — the celebrated crunchy burnt rice at the bottom of the pan.

I put the lid back on the pot and descended into my spot.

Eternity went by before my grandma finally said, “Let’s eat.”

I sat down at her kitchen table, which was covered by a white embroidered tablecloth covered by a large see-through plastic tablecloth. She scooped hefty spoonfuls of the fluffy orange rice into a bowl, and then with elbow grease scraped the bottom of the pot to excavate the pegao, placing the crunchy bits on top of the fluffy rice. She placed the bowl of steaming arroz con gandules with large chunks of tender braised pork shoulder in front of me.

Nana picked up the telephone receiver. “Papo?” she said. I ignored the rest like any well-trained kid did in those days. Food was present, so nothing else existed. I dug into my bowl of rice and happily chomped away; tender pieces of braised pork shoulder, brightness from the olive brine, musk from the achiote, floral from the recao, each rice kernel separated and yet coagulated and finished off with the crunchiness of the pegao. I silently dug into my arroz con gandules while fingering the pinto bean left on the photo of a sandia on my loteria card.

After that day, my uncle Papo came around to the compound more than ever. He spent entire days working on my mom’s car, which seemed to run just fine whenever we’d use it on an errand.

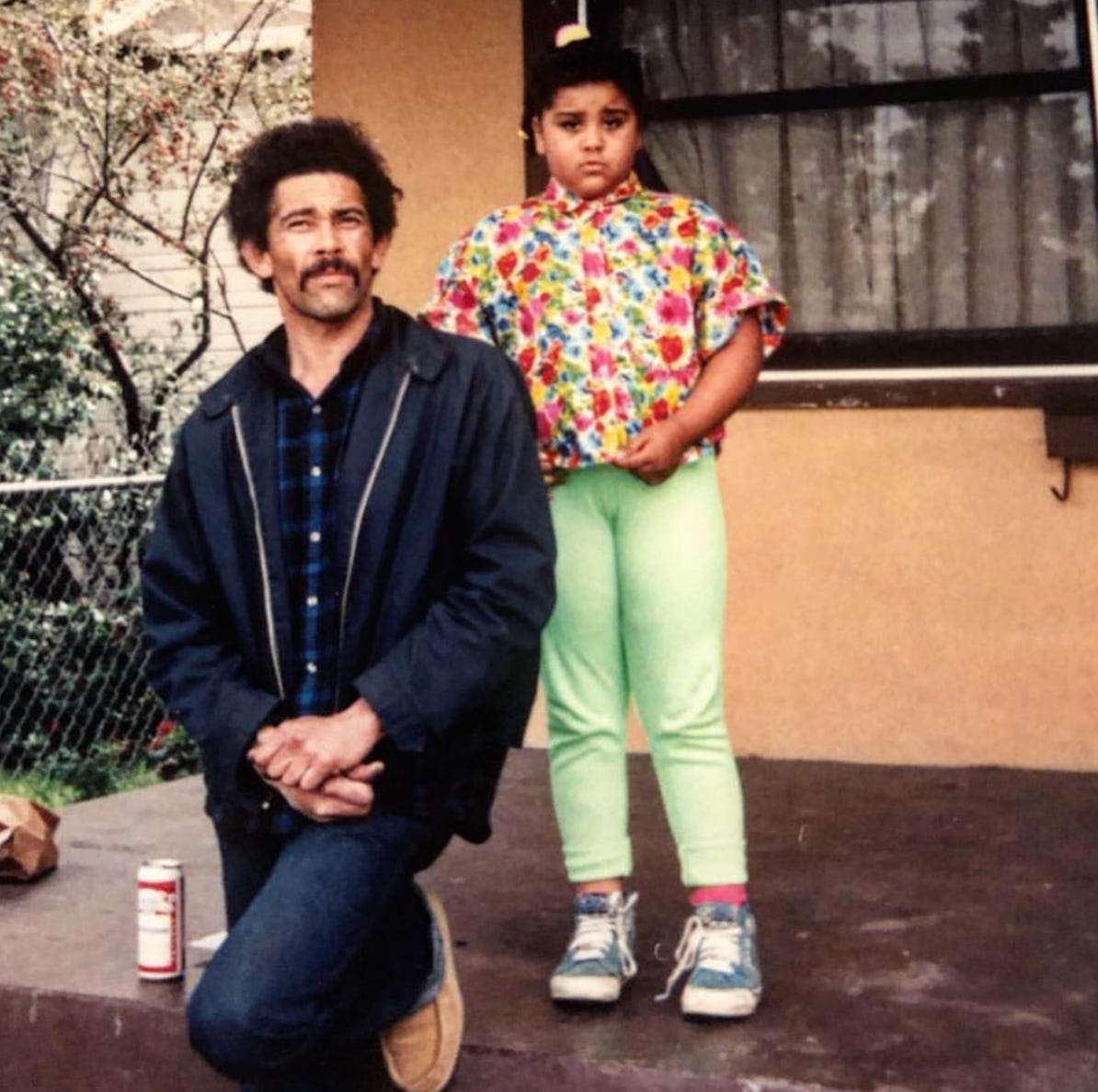

Above Image: 1991. Me and Uncle Papo standing in front of my Nino’s Ephraim’s house in Oak Park, Sacramento.

One day, I was holding the water hose for him while he washed his hands with Ajax, attempting to scrub away the dirt and oil that had caked in the lines on his palms. Looking straight passed me, his eyes suddenly became fiery and fixed. When I turned around, I laid eyes on Vicente walking up the next-door driveway. “Can you get me a towel, mija?” Uncle Papo said. I ran inside and looked for car rags, but by the time I came back, Papo was gone. I never saw Vicente after that. And it was several months until I saw my Uncle Papo again.

In my memories, I still see Vicente’s smile and what he did to my mom. I keep asking myself, though: Why didn’t I do anything in that immediate moment?

Arroz con Gandules

Serves 4

1 pound boneless pork shoulder ribs (also labeled as “country ribs”)

Salt and pepper to taste

1 cup long grain rice

½ cup sofrito < click for recipe

¼ cup tomato sauce

2 tablespoons Sazon con Culantro y Achiote

¼ cup Manzanilla olives (with the pits)

1 15-ounce can gandules

2 tablespoons canola oil

Instructions: Season the ribs with salt and pepper and cut into ½-inch chunks. Set aside.

Wash the rice twice to remove impurities and some of the starch. Set aside.

In a large mixing bowl, combine sofrito, tomato sauce, sazon, gandules, olives and 1 cup water. Set aside.

In a large pot or deep pan, heat canola oil over medium heat. Sear meat until crispy and brown. You may have to do this in batches. Remove meat from pot and set aside.

Place rice into the pot with the pork fond and stir until the rice has absorbed the oil, about 30 seconds. Add the sofrito mixture to the pot with the rice. Stir. Season with salt to taste. Add meat back into the pot, stir and bring to a boil. Reduce heat to medium-low and cover. You don’t want the heat too high, but you do want to form the pegao at the bottom of the pot. Simmer for 20-30 minutes until the rice is cooked through and the meat is tender.

Thank you Illyanna Maisonet. Your story was very powerful for me. It reminded me of a very special book I take out around November each year and read the stories through Jan 6. Las Christmas. Favorite Latino authors share their Holiday Memories. Edited by Esmeralda Santiago. I cherish this book. Each story has a favorite recipe. I feel so glad that I was introduced to you by my daughter. Best to you always.

The way you describe your nana cleaning the rice is the same way my mom does it. It's so interesting to see how food molds us growing up. The way you tell the story makes me feel like I am there too.